38 ISE Magazine | www.iise.org/ISEmagazine

After nearly 40 years of intensive observation of

manufacturers and their attempts to implement

just-in-time (JIT) production, lean manufactur-

ing or Toyota Production System, I’m attempting

to apply my industrial engineering skill set (such as

it is) to sort out some of the good, the bad and the

muddled. In this article I’ll pick out a few highlights of that re-

search seen in years past, with first emphasis on methodologies.

While other researchers with similar aims have relied on

survey research, mine is based on first-hand observation in

which I’ve taken detailed notes, all under the general category

of simplification. First, we consider unique examples of sim-

plicity. Second are simplifications that are manifest in cellular

manufacturing. The third is of configuring or reconfiguring

the factory with simpler productive equipment, which entails

withdrawing “monument” equipment in favor of “lean” ma-

chines.

Each of the three is potent in itself. When combined they

become a dominating competitive force.

Unique examples of simplicity

As unique examples of simplicity I’ll refer to four manufactur-

ers, Precor, Alstrom, Hon and Mark Andy.

Precor. I visited the Bothell, Washington, plants of this

producer of high-end fitness equipment in 1991. The com-

pany’s demand pattern for its retail “bikes” (treadmills, station-

ary bikes, etc.) is seasonal but otherwise fairly regular. For its

heavy-duty commercial bikes, ordered by contract, demand is

highly irregular. Helping to cope, bike assembly was on stubby

lines with cross-trained assembly teams using a uniquely sim-

Four decades of manufacturing’s hits,

misses and smiles

Plant tours from years past highlight lean, JIT and TPS implementers and their methodologies

By Richard J. Schonberger

A

September 2019 | ISE Magazine 39

ple system for ensuring predictably quick production and with

built-in process improvement. In each line (or cell) each cross-

trained, job-rotating member would hit a button on comple-

tion of a task, those hits displayed on an overhead screen. If one

of the stations kept showing up as slowest to finish, that station

(not the assembler) was seen as problematic and marked for

process improvement.

Precor’s way of quickly and reliably feeding those assembly

cells with machined parts was also rather unique. When pro-

duction began on a big contract, there was minimal delay in

machining the many component parts. That is because key

machine tools are dedicated (with minimal or zero setup time)

to narrow families of parts, owed to use of lower-cost conven-

tional equipment for which high utilization is unimportant.

These methods of delivering a flexibly quick response offer

sizeable competitive advantages, inasmuch as most high-mix

manufacturers of large metal items are mired in the batch-

and-queue mode.

Along with those innovative practices, Precor employed

simple, visual scheduling and material movement and kanban

deliveries from suppliers.

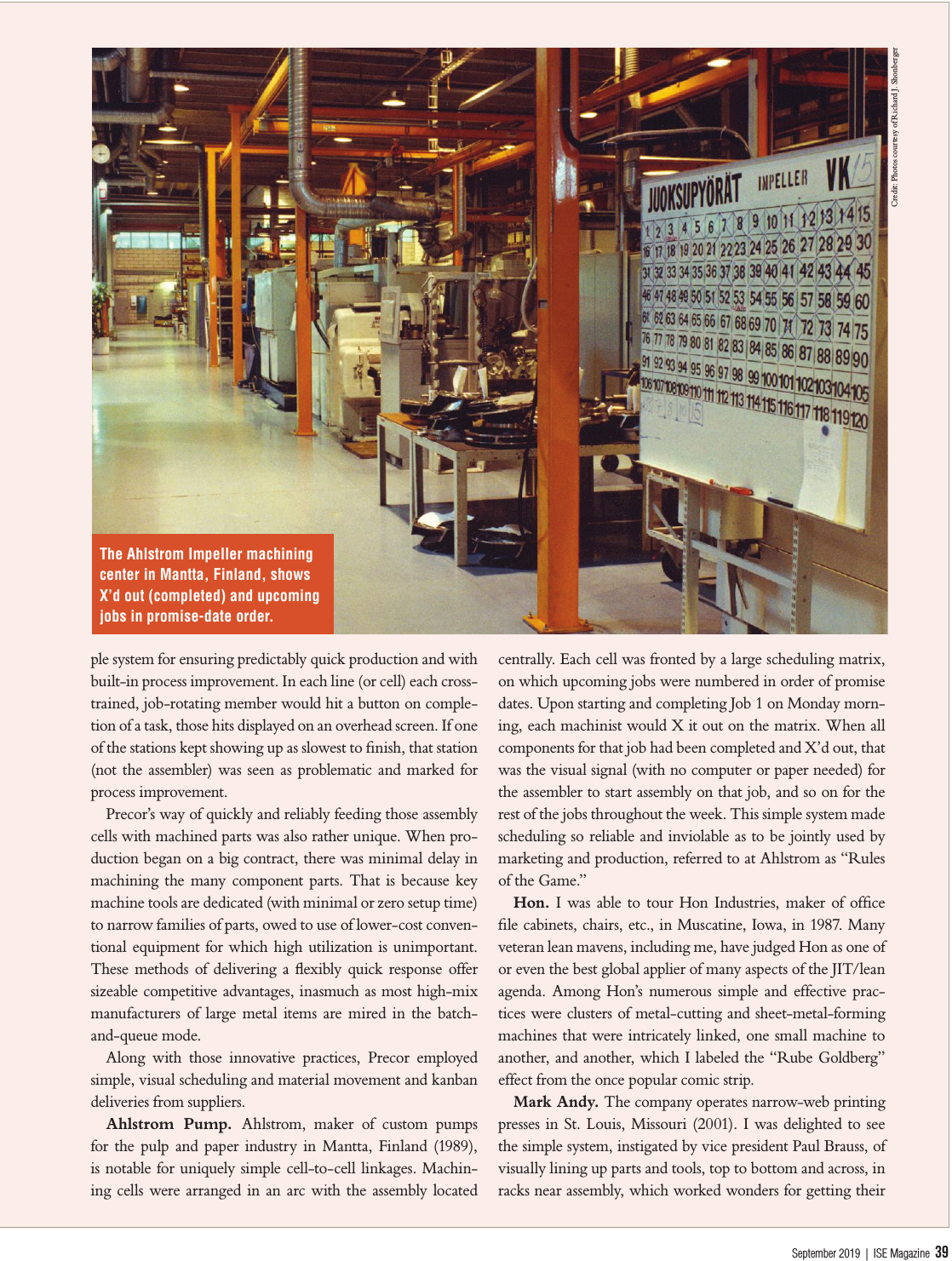

Ahlstrom Pump. Ahlstrom, maker of custom pumps

for the pulp and paper industry in Mantta, Finland (1989),

is notable for uniquely simple cell-to-cell linkages. Machin-

ing cells were arranged in an arc with the assembly located

centrally. Each cell was fronted by a large scheduling matrix,

on which upcoming jobs were numbered in order of promise

dates. Upon starting and completing Job 1 on Monday morn-

ing, each machinist would X it out on the matrix. When all

components for that job had been completed and X’d out, that

was the visual signal (with no computer or paper needed) for

the assembler to start assembly on that job, and so on for the

rest of the jobs throughout the week. This simple system made

scheduling so reliable and inviolable as to be jointly used by

marketing and production, referred to at Ahlstrom as “Rules

of the Game.”

Hon. I was able to tour Hon Industries, maker of office

file cabinets, chairs, etc., in Muscatine, Iowa, in 1987. Many

veteran lean mavens, including me, have judged Hon as one of

or even the best global applier of many aspects of the JIT/lean

agenda. Among Hon’s numerous simple and effective prac-

tices were clusters of metal-cutting and sheet-metal-forming

machines that were intricately linked, one small machine to

another, and another, which I labeled the “Rube Goldberg”

effect from the once popular comic strip.

Mark Andy. The company operates narrow-web printing

presses in St. Louis, Missouri (2001). I was delighted to see

the simple system, instigated by vice president Paul Brauss, of

visually lining up parts and tools, top to bottom and across, in

racks near assembly, which worked wonders for getting their

The Ahlstrom Impeller machining

center in Mantta, Finland, shows

X’d out (completed) and upcoming

jobs in promise-date order.

Credit: Photos courtesy of Richard J. Shonberger

40 ISE Magazine | www.iise.org/ISEmagazine

Four decades of manufacturing’s hits, misses and smiles

complex presses assembled quickly and accurately.

Simplicity is of a unique kind in each of those four com-

panies. Three of them, Precor, Ahlstrom and Hon, combine

their one-off simplifications with a far more common kind,

namely their production being organized into cells. Cellular

production is the second of the three broad methodologies

taken up in this article.

Doing cells right – or not

Cellular manufacturing should be seen as the most far-reach-

ing of methodologies making up lean/JIT. When scattered

processes are brought together to form cellular clusters, each

dedicated to its own family of products (or customers), many

benefits easily come to mind: faster throughput, shorter flow

distances, fewer hand-offs, smaller transport lots, smaller in-

process lots, less in-process inventory, less damage, improved

ergonomics and quicker discovery and correction of defects.

Also, being product family dedicated, product-to-product

changeovers are simplified, even eliminated. Further, cell team

members readily become cross-trained within the cell and be-

fore long with adjacent cells, paving the way to their effec-

tive engagement in process improvement, as well as providing

flexibility to adapt to demand changes. Those improvements

are accompanied by reductions in or elimination of transac-

tions for scheduling, material movement, time-keeping, labor

charging and product costing. In effect, a cell can be treated as

a cost-containment center, a simple alternative to conventional

heavy-handed and error-prone overhead allocation methods

of product costing.

Many or most of the manufacturers I have visited over the

years have at least made a start on implementing cells. The fol-

lowing are a few manufacturers that have done well with cells,

and a few that have stumbled. In best-practice cell design, cell

team members work standing up and may take a few steps in

every cycle to handle two adjacent stations.

Especially well done were the following:

O.C. Tanner, maker of custom-built recognition-award

“emblems” in Salt Lake City, Utah, was visited in 2003. Tan-

ner, a popular visit site for “industrial tourism,” might be seen,

figuratively, as grand champion in the Shingo Institute’s pan-

theon of winners of a Shingo Prize in manufacturing. Over

10 years, Tanner evolved to ever greater numbers of dedicated

cell teams, cutting order fill times from 12 weeks to about two

hours.

AmorePacific, a cosmetics company in Suwon, Korea

(2003), is a standout in its consumer-packaged-goods (CPG)

sector. Nearly all CPG companies perform fill-and-pack on

one or two long conveyor lines. Amore bucked that system,

replacing its own very long line with 23 stubby, minimally au-

tomated cells with stand-up assemblers. This slashed finished

goods inventories and lead times, which led to AmorePacific

eliminating all of its sales reps and agents.

Johnson Controls Interiors, a maker of automotive interiors

in Holland, Michigan, was visited in 1999 and exemplified

a major difference between automotive assemblers and their

components producers. Vehicle assembly was done on a few

At Mark Andy in St.

Louis, each rack is

used for a different

subassembly and

all parts and tools

are arranged in

order of use.

September 2019 | ISE Magazine 41

long, long assembly lines, components com-

monly produced in multiple product family-

dedicated cells. At JCI, the cells were contained

within seven focused factories; for example, 25

cells were for sun visors, in which cut-and-sew

operations were cellular.

East Bay Generator, a remanufacturer of

auto parts in North Oakland, California (1990),

parlayed adoption of cells throughout to reduc-

ing time for operators to search for parts from six

hours daily to zero.

At Fluke Corp., which produces multime-

ters and scopes in Everett, Washington (2003),

cellular production was extensive: 75 or 80 cells

with packout as last operation.

At Wheelabrator blast-wheel machines in

LaGrange, Georgia (1992), I was shown cells

upon cells, and a production/marketing cellular

focus on high-margin “golden-flow” products.

At Rotary Lift, maker of hydraulic hoists for

automotive service in Madison, Indiana, (1993),

each of five cells even had its own paint line.

Plamex, which produces headsets, mikes

and amps in Tijuana, México (1995), set up the

plant in flow-line assembly modules. Corporate

gave support for a pilot-test cell in 1999. In a

phone call in 2000, plant manager Alejandro

Bustamante said they had finally implemented

a few cells, though still with operators sitting on

chairs.

Examples of not, scarcely or minimally done:

A sports uniform maker in Alabama (1988)

proudly showed off a special cell for “zero” lead

time sewing of lucrative professional basketball

uniforms. My question: Since it’s so simple and

effective, in about all respects, why not go cel-

lular for all other products? But globally, cut-

and-sew is chained to grossly ineffective batch-

and-queue methods (the exception being JCI,

discussed above).

A guitar-maker in California (2001) whose

vice president and his staff became enthused

about cellularizing production, entailing short

handoffs from station to station. Yet the plan

went nowhere and at least one of his team re-

signed.

My seminar class and I visited a personal

computer company in the Shanghai area of

China (2008), and in a pre-tour orientation by

managers we were told we would see plentiful

cells. There were no cells, just typically long as-

sembly lines.

The father of the Toyota system

of manufacturing

The origins of the Toyota Production System

began in the late 19th century, not with

automobile production but with textiles.

Sakichi Toyoda, born in 1867, was founder

of Toyota Industries Corp. – the company later

changed its name to “Toyota,” which in Japanese

required only eight pen strokes, considered a

lucky number. He passed down his business

ideals to his son, Kiichiro, and engineer Taiichi Ohno, which later became the

Toyota Way, https://link.iise.org/ToyotaWay.

Those ideals later became part of the Toyota Production System of lean

manufacturing, just-in-time production and kaizen continuous improvement

methods, as adopted by industrial engineers Taiichi Ohno and Eiji Toyoda

between 1948 and 1975. It is steeped in the philosophy of the elimination of all

waste and traces its roots to Sakichi Toyoda’s loom innovations.

Sakichi’s father Ikichi was a farmer and skilled carpenter, and Sakichi began

working for him after he graduated from elementary school. As he matured,

Sakichi became interested in machinery and inventing ways to improve on

traditional methods. In particular, he focused on the hand loom used by

farm families to weave cloth. Through trial and error, he invented a wooden

hand loom and received his first patent in 1891 at age 24. The Toyoda hand

loom required only one hand to operate instead of two, improved quality and

increased efficiency by 40 to 50 percent.

Toyoda then turned his attention to power looms and in 1896 perfected

Japan’s first model built of steel and wood. After his businesses experienced

up and down success for several decades, his Toyoda Automatic Spinning and

Weaving Mill grew from improving economic conditions during World War I.

He worked with Kiichiro to create an automatic loom, perfected as the Type G

in 1924. It delivered the world’s top performance in terms of productivity and

textile quality and a few working models remain on display today.

Sakichi Toyoda died in 1930, five years before his company entered

the automobile business. His Toyoda Automatic Loom Works’ Articles of

Incorporation stated that a major objective of the company “shall be pursuing

related invention and research.” From that came his “Toyoda Precepts”

established in 1935 and followed today:

• Always be faithful to your duties, thereby contributing to the

company and to the overall good.

• Always be studious and creative, striving to stay ahead of the times.

• Always be practical and avoid frivolousness.

• Always strive to build a homelike atmosphere at work that is warm

and friendly.

• Always have respect for spiritual matters, and remember to be

grateful at all times.

42 ISE Magazine | www.iise.org/ISEmagazine

Equipping or re-equipping the factory

For cellular manufacturing to do its main job, which is to serve

up flexibly quick customer responsiveness, there must be sev-

eral or many cells, each product-focused so as to deliver con-

current production – that is, produce multiple products and fill

multiple orders at the same time, closely in tune with market

demand. But how can a manufacturer afford to equip all those

cells with the necessary equipment?

The answer is to phase out the monuments, lean’s term for

big, fast, complex, costly, temperamental equipment that is

designed to produce many different models but only one at

a time. The result of that monument-ma-

chine mode is batch-and-queue produc-

tion of enlarged, wrongly mixed down-

stream inventories, long order-fill lead

times and poor market response. Cellular

manufacturing replaces the monuments

with multiples of smaller, slower, cheap-

er, simpler, more dependable equipment

units, each dedicated to its own cell and

product family. (Note: The author wrote

of the benefits of smaller, more flexible

manufacturing equipment in a June 2017

ISE article, “With machinery purchases,

small can be beautiful,” found at link.iise.

org/ISEJune2017Shonberger.)

All eight of the manufacturers cited

above under “especially well done” cel-

lular manufacturing are equipped with such simpler equip-

ment. O.C. Tanner and Amore-Pacific, being largely hand-

touch producers, have it easy since their equipment is minimal

and inherently small-scale. On the other hand, Wheelabrator

and Rotary Lift produce large, heavy products so each of their

multiple cells had its own metal cutting equipment, largely

affordable, modest-sized versions. As stated earlier at Rotary

Lift, “each of five cells had its own small-scale paint line” in

sharp contrast with the norm of one big, long paint line that

loops across one wall and down another.

In many industries, notably consumer packaged goods

(CPG), monument equipment is entrenched, so much so that

scarcely any company even considers the lean formula: multi-

ple scaled-down units of their fill-and-pack equipment. When

I visit such plants, I’m ready with arguments for re-equipping

their factories through downscaling. Here are four examples,

which involved serious speculations but to my knowledge not

any implementations.

A brewery in Krakow, Poland (2008). As part of a company

conference, my role included a tour one of the giant com-

pany’s best breweries. The plant was equipped, as is the norm

in the sector, with very long and wide high-speed bottling and

canning lines, and few of them. The plant visit led to discus-

sions of a re-equipment strategy: replace the monument lines

with multiple smaller, simpler, slow-paced stubby lines, each

product-family dedicated.

The plan drew favor with high-ranking company people in

attendance, but according to what I learned months later, there

were no implementations. The implication – until it “leans

out” its equipment, the whole bottling and canning industry

will continue being out of step with consumer demand, the

visual evidence being empty shelves in retail stores along with

gluts of less popular items stacking up in warehouses.

A company making coaters for high-end colored/imaged

film in Oklahoma (1986). The plant’s most critical piece of

equipment was a big, complex, tempera-

mental coating machine that required 37

steps to complete a product changeover,

necessitating long runs of each product

between changes. The high point of the

visit was when some of plant’s engineers

came up with the prospect and debated

the technical feasibility of running two

different products side-by-side on the

too-wide coating machine. Thus, in the

future always buy simpler, smaller-scale

coaters.

A maker of confectionary products in

the Netherlands (1989). In this candy

bar plant, the wide forming and coating

machine had characteristics similar to

the coating machines, and the engineers’

speculation on running two products side-by-side suggested

itself; that is, modifying the extrusion and forming equipment

to run two different candy bars side-by-side. And, as with

both of the previous examples, they should evolve to multiple,

dedicated, stubby fill-and-pack lines.

A maker of synthetic insulin in Indianapolis, Indiana (1996).

Here I encountered what I thought to be among the world’s

largest-scale (non-petro) single pieces of production equip-

ment. This equipment producing the drug was a complex net-

work of reactors, sterilizers, pipes, tanks, valves and mixers. Its

dozens of alternate through-paths introduce many sources of

process variation and requires elaborate scheduling and control

systems. Because the single machine included multiples of each

kind of equipment all piped together, they needed a way of

separating the whole thing into two or more flow paths, each

acting like a machine within the machine suggested itself. I am

unaware whether any of the technical or managerial staff ever

looked into this suggestion.

Miscellaneous further examples

I could go on citing more visited facilities revolving around

further lean/JIT process-improvement topics, which is a fairly

long list: quick setup, kanban, visual management, cross-train-

ing/job rotation, job classifications, fail-safing, behavior-based

The Plamex plant in Tijuana,

Mexico, for automated (powered

slide line) cell headset

subassemblies.

Four decades of manufacturing’s hits, misses and smiles

September 2019 | ISE Magazine 43

safety, ergonomics and standup (no chairs) assembly, design

for manufacture and assembly (DFMA), total productive

maintenance (TPM), supplier partnership, costing/accounting

implications, supplier (vendor)-managed inventory, trucks as

warehouses, “make to a number and stop,” end-of-the-quarter

push, continuous replenishment, employee and supplier cer-

tification, performance measurement/management, elimina-

tion of fork trucks, conveyors, material handlers, inspectors

and WIP tracking, and more.

Nearly all of these methodologies, different as they seem,

result in or bring about simplicity. And most of the manufac-

turers featured in this article employ many of these additional

JIT/lean methods and practices.

If all this sounds excessively serious in tone, how about fun,

humor and smiles? Here are three examples of practices that

are both effective and fun to do and to show off.

Roller-skate kanban at Sentrol, motion and smoke de-

tectors in Tigard, Oregon (1992). Assembly took place in 13

dedicated cells, each requiring about 200 different parts. The

big job of supplying the parts from central stores was by a team

of material handlers on roller-skates, which is eight times faster

than walking. They would collect an empty container at an

assembly cell, skate to stores, swap the empty for a full one and

skate back to the assembly cell to place it on the kanban square

for filled containers. Work-in-process inventory fell from six

weeks to four hours.

Mr. SMED at FCI, electronic connectors in Ciudad

Juárez, México (2004). The plant’s changeover expert and fa-

cilitator was known as Mr. SMED (single-minute exchange

of die). Garbed in a yellow hard hat and smock labeled “Mr.

SMED,” he went around assisting and training operators of the

plant’s dozens of mold-presses and other equipment. I took a

photo of him in front of a setup-timing clock and setup tools.

It was working: Changeover times on the mold-presses had

been cut from three hours to 45 minutes.

Kanban is entrenched at Johnson Controls EMSU,

of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (1990), where I took a photo of a

place on the floor in which even the dust and the broom were

marked off as kanban squares.

Other examples of fun and humor have been minimal.

Rather common, though are examples of wry humor. Here

are three.

By car on the way from the airport to Miller Brewing in

Trenton, Ohio (1993), my host, plant manager Dennis Puffer,

said, wryly, “You’re going to hate my plant.” And I did; he

did, too. But Puffer and staff made the best of it by use of

the “star-point” system in which production people are cross-

trained in five functional support areas, one being administra-

tive (budgets, costs, purchasing, time and attendance, over-

time coordination and record-keeping).

How they could find time for all that training and then put

it to use required scheduling in a remarkably innovative way:

By paying all production operatives for nine instead of eight

hours per day (five hours a week of overtime rates) all year

long. It paid off in high rates of process improvements. And

this plant produced about the same amount of beer as similar-

sized breweries but with about half as many employees.

At Apple Computer in Fremont, California (1988), while

touring the receiving area, I asked if all incoming parts had to

be put into the large and growing automated tote stacker. The

answer was yes. “Even parts that are to be used in assembly the

same day?” I asked, with raised eyebrows and a wry smirky

smile. That exchange led to the suggestion to stage at receiv-

ing empty, labeled kanban containers so that parts needed the

same day would avoid the stacker and go direct to points of

use. The next step: Start shrinking the size of the stacker.

At BMW Engines’ largest engines plant in Steyr, Austria

(2011), machining of crankshafts was done on about seven

side-by-side, multistation “lanes,” each with high station-to-

station automation. Machining of any crankshaft was sched-

uled on any of the lanes, and when one station faltered, the

job automatically moved to a station in a sister lane. As we

(myself with a bunch of academics) were moving on from

crankshafts, the tour guide was asked if they had one or more

dominant engine models that could be dedicated to run on

a less-automated lane. His wry reply: “BMW likes to make

things complicated.”

As a brief epilogue, among my more recent plant visits

was one in 2014 to Electroimpact, a massive-scale automat-

ed tooling equipment, e.g., handling entire airplane wings,

in Mukilteo, Washington. I’ll not attempt here to explain

about this amazingly unique manufacturer except to say that

much or most of its employees are engineers who take on an

unheard-of breadth of dedicated-to-customer responsibility.

When I was a young practicing IE, would I have relished that

much responsibility? Hmm.

Richard J. Schonberger is author of some 200 articles and 16

books, including “Japanese Manufacturing Techniques” (Free

Press, 1982) and “World Class Manufacturing” (Free Press,

1986). Full details of his plant visits are available in his latest book,

“Flow Manufacturing – What Went Right, What Went

Wrong: 101 Mini-Case Studies that Reveal Lean’s Successes

and Failures” (Productivity Press/Routledge/Taylor & Francis,

2018). Following early years as a practicing industrial engineer, he

joined the faculty of the University of Nebraska, becoming George

Cook (chaired) professor in operations management and informa-

tion systems, and later affiliate professor in management science at

the University of Washington. His honors include 1995 Academy

of the Shingo Prize; 1990 British Institution of Production En-

gineers’ International Award in Manufacturing Management; and

1998 IIE Production and Inventory Control Award. Schonberger is

on several editorial and governing boards, including IISE’s Industry

Advisory Board.