40 ISE Magazine | www.iise.org/ISEmagazine

The question, “What are the signs operational excel-

lence has succeeded in an organization?” has elic-

ited a variety of responses over the past 40 years. To

some, it is an improvement in quality and customer

satisfaction. To others, it is a reduction in waste and

variability. To yet another group of practitioners, it is

sustainability and enhanced productivity.

The philosophy of operational excellence, in all its flavors,

has undoubtedly influenced the way we approach the art and

science of industrial engineering.

But is there a better way to phrase this question?

Drawbacks to the traditional

operational excellence mindset

Evidence of the burden operational excellence strategies can

place on people has long been hiding in plain sight. Take the

example of lean, one of the great success stories in operational

excellence in the past few decades. Industry and academic ex-

perts underscore the importance of “getting it right,” to avoid

the clear and present risk of implementation fatigue or failure.

The numbers tell a story of sustainability percentages that get

smaller each passing year after implementation, forcing orga-

nizations to introspect what wrongs could be righted the next

time around.

Consider the growing momentum of Industry 4.0 and its

redoubtable promise of better utilization of data and resources

in the pursuit of improved productivity. Technologies to sup-

port Industry 4.0 continue to mature, yet at the highest levels

of inquiry, such as the National Science Foundation and its Future

of Work program, efforts to understand the impact of the im-

pending technological disruption on workforce skill acquisi-

tion and mental preparedness are being encouraged.

The fabric that binds an operational excellence strategy to

the workforce is often frayed. This is not surprising when we

consider operational excellence from the viewpoint of the peo-

ple who implement it and are most impacted by it. When or-

ganizations think about improving productivity, indeed when

entire countries think about improving productivity, they con-

sider an upward tick in the number of working hours as the first

positive sign of change. Yet, data from the World

Bank show that the most productive countries

usually work a lower number of hours than

their lesser productive counterparts.

Regardless, people designing operational

excellence strategies assign more tasks or

more working hours to themselves and

their peers. This is the widespread no-

tion of operational excellence in the

U.S., a country in which most em-

ployees expe-

rience fatigue

at work, as the

National Safety

Council points out

in its 2017 report. Is this where we

want to lead a society already coping

with increasing challenges in mental

health and opioid dependence?

Perhaps it is time for an industrial

engineering practitioner to recognize

that productivity and quality of life

must go hand in hand. The ques-

tion that must be asked is: What

are the signs that operational

excellence has improved

employee quality of life in

an organization?

Toward people-centric

operational excellence

This was the question that my team and

I began to investigate about a decade ago at

the University of Tennessee. This investigation

quickly led to my reaching a fork on the road as

a researcher in operational excellence. One path

led to the pursuit of tactical goals and incremental

contributions to well-studied topics such as lean tools,

work design and applied optimization. In this pursuit, the

inclusion of people-specific factors such as culture, stress, en-

gagement and motivation would be considered tangential or

incidental to the success of a project.

The other path led to pursuing strategic goals that would

challenge our team to define transformational actions in an

organization. We would place employee quality of life in the

spotlight and, along with productivity, make it an inalienable

criterion for success in an operational excellence framework.

It was clear to us which path aligned more closely with our

philosophy of operational excellence.

Nevertheless, any process of creating a new operational

excellence model requires translating ideas into strategy and

strategy into actionable targets. We based our journey on two

T

The fabric that binds an operational

excellence strategy to the workforce is often

frayed. This is not surprising when we

consider operational excellence from the

viewpoint of the people who implement it

and are most impacted by it.

January 2021 | ISE Magazine 41

The Sawhney Model:

Operational excellence for the people,

by the people

Plan’s 4 modules align Industry 4.0 goals with workers’ quality of life

By Rupy Sawhney, Ninad Pradhan, Enrique Macias de Anda and Carla Arbogast

42 ISE Magazine | www.iise.org/ISEmagazine

The Sawhney Model: Operational excellence for the people, by the people

industrial engineering pillars.

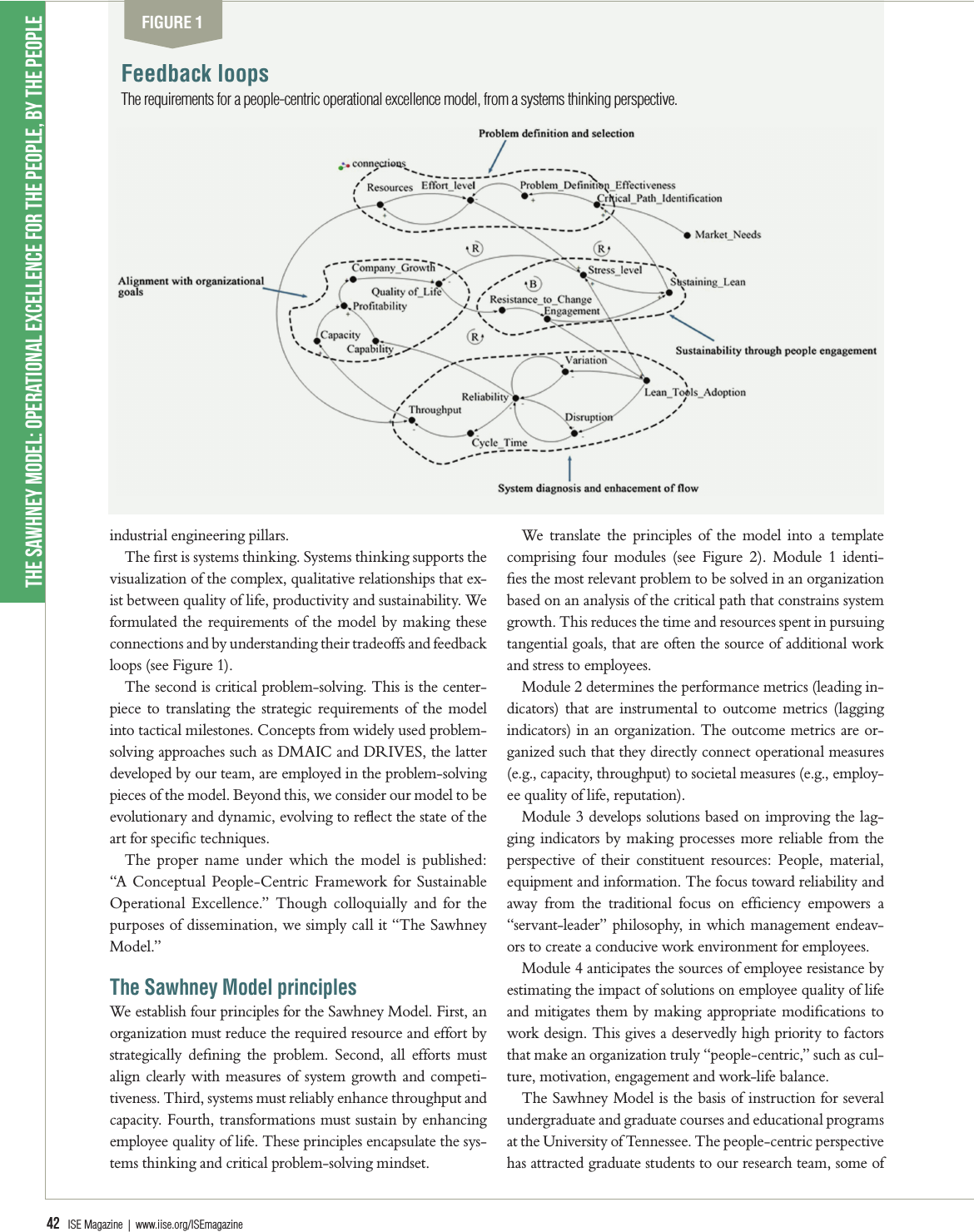

The first is systems thinking. Systems thinking supports the

visualization of the complex, qualitative relationships that ex-

ist between quality of life, productivity and sustainability. We

formulated the requirements of the model by making these

connections and by understanding their tradeoffs and feedback

loops (see Figure 1).

The second is critical problem-solving. This is the center-

piece to translating the strategic requirements of the model

into tactical milestones. Concepts from widely used problem-

solving approaches such as DMAIC and DRIVES, the latter

developed by our team, are employed in the problem-solving

pieces of the model. Beyond this, we consider our model to be

evolutionary and dynamic, evolving to reflect the state of the

art for specific techniques.

The proper name under which the model is published:

“A Conceptual People-Centric Framework for Sustainable

Operational Excellence.” Though colloquially and for the

purposes of dissemination, we simply call it “The Sawhney

Model.”

The Sawhney Model principles

We establish four principles for the Sawhney Model. First, an

organization must reduce the required resource and effort by

strategically defining the problem. Second, all efforts must

align clearly with measures of system growth and competi-

tiveness. Third, systems must reliably enhance throughput and

capacity. Fourth, transformations must sustain by enhancing

employee quality of life. These principles encapsulate the sys-

tems thinking and critical problem-solving mindset.

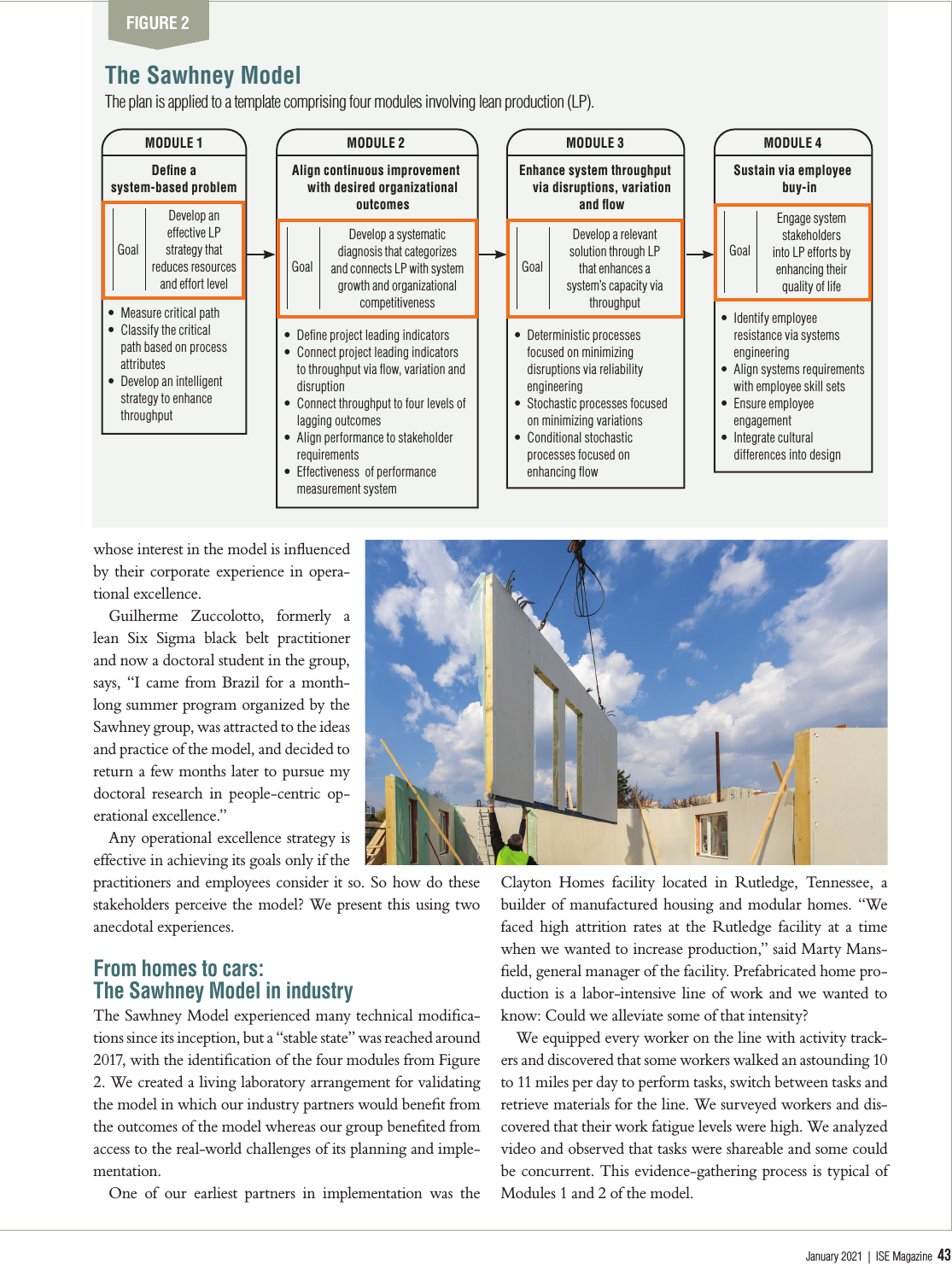

We translate the principles of the model into a template

comprising four modules (see Figure 2). Module 1 identi-

fies the most relevant problem to be solved in an organization

based on an analysis of the critical path that constrains system

growth. This reduces the time and resources spent in pursuing

tangential goals, that are often the source of additional work

and stress to employees.

Module 2 determines the performance metrics (leading in-

dicators) that are instrumental to outcome metrics (lagging

indicators) in an organization. The outcome metrics are or-

ganized such that they directly connect operational measures

(e.g., capacity, throughput) to societal measures (e.g., employ-

ee quality of life, reputation).

Module 3 develops solutions based on improving the lag-

ging indicators by making processes more reliable from the

perspective of their constituent resources: People, material,

equipment and information. The focus toward reliability and

away from the traditional focus on efficiency empowers a

“servant-leader” philosophy, in which management endeav-

ors to create a conducive work environment for employees.

Module 4 anticipates the sources of employee resistance by

estimating the impact of solutions on employee quality of life

and mitigates them by making appropriate modifications to

work design. This gives a deservedly high priority to factors

that make an organization truly “people-centric,” such as cul-

ture, motivation, engagement and work-life balance.

The Sawhney Model is the basis of instruction for several

undergraduate and graduate courses and educational programs

at the University of Tennessee. The people-centric perspective

has attracted graduate students to our research team, some of

FIGURE 1

Feedback loops

The requirements for a people-centric operational excellence model, from a systems thinking perspective.

January 2021 | ISE Magazine 43

whose interest in the model is influenced

by their corporate experience in opera-

tional excellence.

Guilherme Zuccolotto, formerly a

lean Six Sigma black belt practitioner

and now a doctoral student in the group,

says, “I came from Brazil for a month-

long summer program organized by the

Sawhney group, was attracted to the ideas

and practice of the model, and decided to

return a few months later to pursue my

doctoral research in people-centric op-

erational excellence.”

Any operational excellence strategy is

effective in achieving its goals only if the

practitioners and employees consider it so. So how do these

stakeholders perceive the model? We present this using two

anecdotal experiences.

From homes to cars:

The Sawhney Model in industry

The Sawhney Model experienced many technical modifica-

tions since its inception, but a “stable state” was reached around

2017, with the identification of the four modules from Figure

2. We created a living laboratory arrangement for validating

the model in which our industry partners would benefit from

the outcomes of the model whereas our group benefited from

access to the real-world challenges of its planning and imple-

mentation.

One of our earliest partners in implementation was the

Clayton Homes facility located in Rutledge, Tennessee, a

builder of manufactured housing and modular homes. “We

faced high attrition rates at the Rutledge facility at a time

when we wanted to increase production,” said Marty Mans-

field, general manager of the facility. Prefabricated home pro-

duction is a labor-intensive line of work and we wanted to

know: Could we alleviate some of that intensity?

We equipped every worker on the line with activity track-

ers and discovered that some workers walked an astounding 10

to 11 miles per day to perform tasks, switch between tasks and

retrieve materials for the line. We surveyed workers and dis-

covered that their work fatigue levels were high. We analyzed

video and observed that tasks were shareable and some could

be concurrent. This evidence-gathering process is typical of

Modules 1 and 2 of the model.

FIGURE 2

The Sawhney Model

The plan is applied to a template comprising four modules involving lean production (LP).

MODULE 1

Define a

system-based problem

• Measure critical path

• Classify the critical

path based on process

attributes

• Develop an intelligent

strategy to enhance

throughput

Develop an

effective LP

strategy that

reduces resources

and effort level

Goal

MODULE 2

Align continuous improvement

with desired organizational

outcomes

• Define project leading indicators

• Connect project leading indicators

to throughput via flow, variation and

disruption

• Connect throughput to four levels of

lagging outcomes

• Align performance to stakeholder

requirements

• Effectiveness of performance

measurement system

Develop a systematic

diagnosis that categorizes

and connects LP with system

growth and organizational

competitiveness

Goal

MODULE 3

Enhance system throughput

via disruptions, variation

and flow

• Deterministic processes

focused on minimizing

disruptions via reliability

engineering

• Stochastic processes focused

on minimizing variations

• Conditional stochastic

processes focused on

enhancing flow

Develop a relevant

solution through LP

that enhances a

system’s capacity via

throughput

Goal

MODULE 4

Sustain via employee

buy-in

• Identify employee

resistance via systems

engineering

• Align systems requirements

with employee skill sets

• Ensure employee

engagement

• Integrate cultural

differences into design

Engage system

stakeholders

into LP efforts by

enhancing their

quality of life

Goal

44 ISE Magazine | www.iise.org/ISEmagazine

The Sawhney Model: Operational excellence for the people, by the people

It is pertinent to note that we consider

questions like, “What is the step count

per person?” and “What is the stress level

per person?” on par with typical indus-

trial engineering analyses such as “What

is the cycle time?” and “What are the

scheduling opportunities?” Elevating

people-centered metrics to the same level

of importance as production metrics al-

lows us to innovate accordingly in Mod-

ules 3 and 4 (developing and sustaining

solutions).

The solutions for Clayton Homes are

industrial engineering solutions but with

a distinct identity that can only be as-

cribed to the philosophy and organiza-

tion of our model. Consider this list of novel methods designed

and validated for the facility: a work-sharing-based scheduling

algorithm to reduce cycle times; ergonomic workload balanc-

ing to reduce effort; and just-in-time supermarkets to simplify

material availability.

According to Mansfield, “We piloted the approach on one

station and were surprised to see that it motivated people on

other stations to come up with their own versions of it. The

lack of employee resistance to the radical change was remark-

able.” Clayton Homes has seen a dramatic rise in retention

rates, which informally can trace connections to the Sawhney

Model.

The second story takes us to a different work environment

altogether. A day in the life of an automotive supplier facility

is quite distinct from that of a house manufacturer. The cycle

times change from tens of minutes to tens of seconds. We part-

nered with DENSO, a subsidiary of Toyota Motor Co. and a

leading supplier of advanced automotive technology, systems

and components for major automakers that operates its largest

U.S. manufacturing facility in Tennessee.

The company approached us with the challenge of improv-

ing disruption recovery times in one of its manufacturing

cells. The cell comprised six “zones” occupied by one em-

ployee each, the person being responsible for one or multiple

steps in each zone. We interpreted this as a people-centered

work design problem. That is, could we define a set of simple

policies for the employees on the line to improve the recovery

time of the line following a disruption? This reduces the em-

phasis on immediacy and urgency in response to disruptions,

thereby addressing a common job stressor.

Consistent with Module 2 of the Sawhney Model, we fo-

cused on analyzing the zones leading to and following a dis-

ruptive event. The concept of floating bottlenecks, in this case,

was found to be appropriate to capture the variation and dis-

ruptions to the production flow in the cell. We collected 64

hours of data by direct observation and 40 additional hours of

movement data using “indoor GPS” technology. Simulation

models were generated and showed that guiding the reaction

of employees to disruption were key to resolving the issue.

More concretely, we found that the opportunity resided in

deciding the timing of production stoppages following a dis-

ruption at some location in the cell. This counters the intu-

ition and indeed the practice of “stop all work immediately”

following a disruption.

Our simulation models suggest a stoppage policy that while

an immediate stop in the first and fourth zone would enhance

shift throughput by 43% and 10%, respectively, immediately

stopping work in the fifth zone would decrease throughput by

16%. This insight helped us propose a no-cost disruption re-

covery strategy for DENSO that demonstrably improved the

throughput while minimizing employee stress by equipping

workers with simple disruption response policies.

“The focus on simple, low-cost and low-stress policies for

our line workers introduced us to a new perspective on im-

proving throughput while still taking care of the stress on our

employees,” said Dan Dougherty from DENSO.

Perhaps it is time for an industrial

engineering practitioner to recognize that

productivity and quality of life must go

hand in hand. The question that

must be asked is:

What are the signs that operational

excellence has improved employee quality

of life in an organization?

January 2021 | ISE Magazine 45

These are just two of many examples of applying the Sawh-

ney Model in collaboration with our partners. We have five

active projects in which we translate the principles of the mod-

el into practice.

Looking ahead

We anticipate that the next frontier of the Sawhney Model re-

sides in integrating it with information-centric industry frame-

works. Industry 4.0 is an example of a framework used in in-

dustry to connect systems and services and to build a corpus of

data. How do we adapt our model to work with millions of data

points, thousands of employees sharing work and hundreds of

sensors broadcasting data concurrently?

The critical observation is that companies must continue to

focus on problem definition and selection, alignment of metrics

with organizational goals, enhancement of reliability in the sys-

tem and engagement with people. In other words, Industry 4.0

does not disrupt the core objectives of the Sawhney Model but

does pose technical challenges in its implementation.

There are two challenges to resolve. The first challenge is

to enhance individual techniques in the Sawhney Model to

keep pace with the pervasiveness of data; its collection and stor-

age methods must factor into our implementation strategy. A

highly connected system also implies that a small change in one

subsystem can lead to big effects in a different subsystem. We

must identify techniques that can cope with this complexity; for

example, apply machine learning models to make sense of the

interrelationships in the data.

The second challenge is to maintain the integrity of the mod-

el by continuing to be sensitive to the needs of the workforce. In

fact, this challenge may present an opportunity to employ tech-

nology to bolster worker training, for example, using augment-

ed reality. Another opportunity is to provide decision-makers

with a live snapshot of the state of the system and recommend

improvements, analogous to the concept of digital twin and vir-

tual manufacturing that have gained momentum recently.

This is the history, state and future of the Sawhney Model.

It has been a memorable experience translating our ideas into

a people-centric operational excellence model and motivating

to find champions in industry and federal agencies who have

chosen to support our journey. But what drives us is what lies

ahead.

Rupy Sawhney, Ph.D., is a Distinguished Professor and Heath Fel-

low in Business and Engineering at the Department of Industrial and

Systems Engineering with the University of Tennessee, Knoxville,

and executive director of the Center for Advanced Systems Research

and Education. He and his team have partnered with over 200 compa-

nies on operational excellence projects and he has established innovative

educational and training programs with national and international vis-

ibility. He has been recognized with various awards such as the Boeing

Welliver Fellowship, University of Tennessee President’s Award as the

“Educate” honoree and the John L. Imhoff Global Excellence Award

for Industrial Engineering Education. He is an IISE member.

Ninad Pradhan, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral research associate in the De-

partment of Industrial and Systems Engineering at the University of

Tennessee, Knoxville. He is the Research Liaison for the Center for

Advanced Systems Research and Education. His research focuses on

the design of optimization, computer vision and machine learning al-

gorithms for manufacturing and supply chain environments. As the

Research Liaison for CASRE, he works extensively on formalization

of applied research within the center, facilitation of research partnerships

and federal grants, and development of new research directions.

Enrique Macias de Anda, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral research associ-

ate in the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering at the

University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He also serves as industry liaison

within the Center for Advanced Systems Research and Education.

He served as the industrial engineering undergraduate program director

and academic adviser for the Aguascalientes’ Campus of Monterrey’s

Technological Institute of Higher Education. His research focus is un-

derstanding the cultural aspects of operational excellence.

Carla Arbogast, M.S., is director of the Center for Advanced Systems

Research and Education at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Her professional goals are to develop and facilitate long-term partner-

ships with industry and higher education institutions both nationally

and internationally. She has been instrumental in initiating several

educational programs at the center, including certificate and degree pro-

grams. Her research interests are in the study of human factors related

to culture, job stress and workforce development.

Any operational excellence strategy

is effective in achieving its goals only

if the practitioners and employees

consider it so.

Webinar explores

the Sawhney Model

Author Rupy Sawhney discussed his model and the topic

featured in this article in a recent IISE webinar, “How to

Create People-Centered Operational Excellence Strategies.” It

explores how to redesign OpEx programs to improve the value

exchange with employees and other stakeholders. To access

the webinar and upcoming sessions, visit iise.org/webinars.